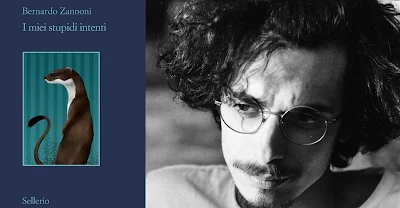

Come se non bastasse il successo italiano ed europeo che il libro di Bernardo Zannoni, "I miei stupidi intenti" ha avuto dopo la recente vittoria al premio Campiello, arriva questo splendido articolo pubblicato sul New York Times che sancisce definitivamente, nel mondo, la valenza del nostro scrittore e la pubblicazione del romanzo" My stupid intentions" in terra americana. Dunque, a seguire la traduzione dell'articolo con Google(con qualche mia correzione) direttamente dal giornale. Dopo l'articolo ho riportato il testo in inglese che, comunque potete trovare QUI in originale.

The Woodland Creature's Guide to Life, Death and Divinity

Il narratore di “My Stupid Intentions”, romanzo d'esordio di Bernardo Zannoni, è una faina in un mondo che non perdona.

(LE MIE STUPIDE INTENZIONI, di Bernardo Zannoni. Tradotto da Alex Andriesse).

Le martore sono carnivori carini ma feroci con un'ampia distribuzione in tutto il mondo, principalmente nelle foreste. Ne esistono otto specie, dalle martore agli zibellini, e tendono ad essere più sfuggenti di molti dei loro parenti più stretti (inclusi tassi, donnole e lontre). Sono anche meno conosciuti; la maggior parte di noi non è in grado di individuare una martora in una fila di creature dei boschi.

Tuttavia, almeno due romanzi sono stati scritti negli ultimi 10 anni con questi piccoli furbearer come protagonisti, il più recente “My Stupid Intentions”, il premiato primo libro dello scrittore italiano Bernardo Zannoni. Questa presunta autobiografia di una faina si unisce a "Martin Marten" (2015) di Brian Doyle, su un ragazzo e una giovane martora nel nord-ovest del Pacifico, nella letteratura emergente di martenkind.

Mentre il personaggio di Doyle vive la vita di un animale selvatico, coinvolto tangenzialmente con gli umani di cui incrocia i percorsi, il narratore di Zannoni, Archy, sembra più un delinquente adolescente con un'etichetta animale schiaffeggiata su di lui. Vive in una cultura sospettosamente umana, anche se cupa: sua madre, non amorevole, cucina i loro pasti e parla di portare i suoi figli dal dottore, anche se ignora la presenza di un cucciolo morto nella sua tana. Dopo che il giovane Archy è rimasto mutilato in una caduta da un albero, dove ha cercato di strappare alcune uova da un nido, la madre lo scambia per un pollo e mezzo morto da una volpe di nome Solomon, un avido prestatore, prestatore di pegno, truffatore artista e boss del crimine (che sa di stereotipo antisemita).

Rifiutato da sua madre, duramente sfruttato e maltrattato in modo egregio da Solomon, Archy alla fine, scopre il tesoro più segreto e prezioso del prestatore di pegni: una Bibbia che è caduta sulla testa di Solomon mentre si stava nutrendo del cadavere di un impiccato.

Solomon ha imparato a leggere da solo e trasmette questa abilità ad Archy, che impara non solo a leggere ma anche a scrivere. Mentre la volpe è ossessionata dalla sua interpretazione della parola di Dio, Archy preferisce la storia delle avventure di Solomon, che è stato incaricato di scrivere. Il suo ruolo di biografo gli offre un disperato aiuto nella necessaria relazione con Salom stesso.

Mentre Salomon racconta il suo passato per il suo scrivano, è desideroso di far vedere il suo cattivo comportamento sotto una luce cristiana, e l'arguzia di Zannoni è spesso più acuta quando si tratta del desiderio dell'astuta volpe di conformarsi alla moralità biblica.

Solomon detta: “'Io rubo galline con Victor e uccidiamo gli altri per divertimento'. Aspetta. “Abbiamo preso una gallina per noi e abbiamo sacrificato il resto al Signore”. Mettila giù così”.

Un cane silenzioso e assassino di nome Joel, che funge da tirapiedi di Solomon, è il guardiano di Archy e talvolta co-cospiratore. I due vagano per la campagna come portaborse di Solomon, brutalizzando e divorando gli sfortunati animali che non pagano. Archy ha le sue tendenze omicide, con impulsi incestuosi e una zuppa di cannibalismo. Col passare del tempo, diventa ancora più feroce.

Il personaggio principale di questa favola succosa e meschina probabilmente non aveva bisogno di essere interpretato come una martora - un essere umano sarebbe stato sufficiente - e come lettori non ci interessa se Archy sia un passabile membro della famiglia delle donnole. Ci interessa invece l'acutezza della sua voce e del suo carattere: la scrittura di Zannoni, nell'elegante traduzione di Alex Andriesse, ha l'amarezza costituzionale di J.P. Donleavy o Louis-Ferdinand Céline.

"My Stupid Intentions" è una storia vigorosa e intensa, anche se non sempre sembra sfumata nei suoi riferimenti alla natura animale o all'indagine teologica. L'idea è che Archy vuole deliziarsi della sua autentica animalità, mentre Solomon vuole emulare un essere umano cristiano; la differenza tra le due categorie sembra avere a che fare con la conoscenza della mortalità, un certo rapporto con un certo tipo di Dio e la vergogna.

Le particolari forme di autocoscienza e sadismo di Archy e Solomon ricordano l'umanità. Se uno di loro ha qualità che appartengono più alle bestie non umane, quelle non vengono mai definite. Quindi l'esplorazione centrale del romanzo è meno del carattere umano o animale che del carattere della divinità, su cui i pensieri di Archy a volte possono risultare un po' confusi:

"Io... ho trovato pace con Dio. Mi era chiaro che il mondo non odia nessuno, e se è crudele è perché noi stessi siamo crudeli. L'unico errore di Dio è stato quello di aver voluto che prendessimo parte alle cose, uomini e animali. Mi sono assolto e ho fatto pace con coloro che mi avevano offeso perché, al di fuori della nostra testa, il dolore non ha peso, perché il male non esiste".

Le riflessioni del romanzo sul libero arbitrio e sulla sofferenza sono oscure, ma c'è una chiarezza potente e fredda negli incontri mortali di Archy con altri animali e nella malizia riflessiva che porta loro. Se il male non esiste, allora la malizia è proprio un fatto di natura.

La versione originale dal New York Times

The Woodland Creature’s Guide to Life, Death and Divinity

The narrator of “My Stupid Intentions,” Bernardo Zannoni’s debut novel, is a beech marten in an unforgiving world.

MY STUPID INTENTIONS, by Bernardo Zannoni. Translated by Alex Andriesse.

Martens are cute but fierce carnivores with a wide

distribution across the globe, mostly in forests. There are eight species of

them, from pine martens to sables, and they tend to be more elusive than many

of their closest relatives (including badgers, weasels and otters). They’re

also less well known; most of us couldn’t pick out a marten in a woodland

creature lineup.

Still, at least two novels have been written in

the past 10 years with these small furbearers as protagonists, most

recently “My Stupid Intentions,” the prizewinning first book by the Italian

writer Bernardo Zannoni. This putative autobiography of a beech marten joins

Brian Doyle’s “Martin Marten”

(2015), about a young boy and a juvenile pine marten in the Pacific Northwest,

in the emergent literature of martenkind.

Whereas Doyle’s character lives a wild animal’s life,

tangentially involved with the humans whose paths he crosses, Zannoni’s

narrator, Archy, seems more like a teenage thug with an animal label

slapped on him. He lives in a suspiciously human culture, albeit a grim one:

His unloving mother cooks their meals and talks about taking her children to

the doctor, even as she ignores the presence of a dead kit in her den. After

the young Archy is maimed in a fall from a tree, where he tried to snatch some

eggs out of a nest, she trades him for one and a half dead chickens to a fox

named Solomon, a greedy lender, pawnbroker, rip-off artist and crime boss (who

smacks of antisemitic stereotype).

Rejected

by his mother, only to be worked hard and egregiously abused by Solomon, Archy

eventually discovers the pawnbroker’s most secret and precious treasure: a

Bible that fell on Solomon’s head when he was feeding on the corpse of a hanged

man.

Solomon has taught himself to read it and passes this

skill along to Archy, who learns not only how to read but also how to write.

While the fox is obsessed with his interpretation of the word of God, Archy

prefers the story of Solomon’s own adventures, which he has been tasked with

writing down. His role as biographer gives him desperately needed leverage in

the relationship.

As Solomon narrates his past for his scribe, he’s keen

to recast his bad behavior in a Christian light, and Zannoni’s wit is often

sharpest when it comes to the sly fox’s yearning to conform to biblical

morality.

Solomon dictates: “‘I steal hens with Victor and we kill the others for fun.’ Wait. ‘We took one hen for ourselves and sacrificed the rest to the Lord.’ Put it down like that.”

A

silent, murderous dog named Joel, who serves as Solomon’s muscle, is Archy’s

warden and sometime co-conspirator. The two of them roam around the countryside

as Solomon’s bagmen, brutalizing and eating the unlucky animals who don’t pay

up. Archy has homicidal tendencies of his own, with incestuous urges and a

soupçon of cannibalism thrown in. As time goes on, he becomes more vicious

still.

The main character in this juicily meanspirited fable

probably didn’t need to be cast as a marten — a human would have sufficed — and

as readers we don’t care whether Archy makes a passable member of the weasel

family. Instead, we care about the sharpness of his voice and character:

Zannoni’s writing, in Alex Andriesse’s elegant translation, has the

constitutional bitterness of J.P. Donleavy or Louis-Ferdinand Céline.

“My Stupid Intentions” is a

vigorous and intense story, even if it doesn’t always seem nuanced in its

references to either animal nature or theological inquiry. The idea is that

Archy wants to delight in his authentic animality, while Solomon wants to

emulate a Christian human; the difference between the two categories seems to

have to do with a knowledge of mortality, a certain relationship with a certain

kind of God, and shame.

Archy’s and Solomon’s

particular forms of self-awareness and sadism are redolent of humanness. If

either of them has qualities that belong more to nonhuman beasts, those are

never defined. So the novel’s central exploration is less of human or animal

character than of the character of divinity, on which Archy’s thoughts can

sometimes come off as a bit confused:

I … found peace with God. It was clear to me

that the world hates no one, and if it’s cruel, that’s because we ourselves are

cruel. God’s one error was to have wanted us to

take part in things, men and animals alike. I absolved myself and made peace

with those who had trespassed against me because, outside of our own heads,

pain has no weight at all — because evil does not exist.

The novel’s musings about free will and suffering are

murky, but there’s a powerful, cold clarity in Archy’s deadly encounters with

other animals and the reflexive malice he brings to them. If evil doesn’t

exist, then malice is just a fact of nature.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento